The United States Supreme Court (SCOTUS) in a recent landmark decision established a Subjective Mens Rea Burden of Proof Under the Controlled Substances Act.

Government must now prove defendant subjectively intended to write illegal prescriptions to convict.

Heath Hyde stays abreast of changes in legislation, government agency regulations, case law, recent Court Rulings and industry trends. Therefore, Federal Criminal Defense Lawyers at Heath Hyde utilizes these new developments in the law to help his clients and then creates timely legal updates to keep clients up to date on legal developments important to their business or ongoing criminal case.

Mens Rea in Healthcare Fraud Cases

A recent Supreme Court decision holding that the government must prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a defendant knowingly or intentionally acted in an unauthorized manner when prescribing controlled substances will benefit doctors and other health care professionals responsible for dispensing controlled substances in accordance with the Controlled Substances Act.

Physicians can now practice with a little less worry that their honest prescribing methods would lead to criminal prosecution and can instead refocus their attention on helping their patients as a result of recent attention on physician overprescribing in the context of the opioid epidemic. In fact, with more work required of prosecutors, the government may (ideally) narrow its focus to the instances or prescribers that are the most problematic.

The legislation, among other things, declares “any person knowingly or willfully… produce, distribute, or dispense, or possess with intent to manufacture, distribute, or dispense a banned substance” to be a federal criminal “except as allowed.” Up to this point, the government merely needed to show that the prescription in question was illegal and that the doctor who issued it did so knowingly or willfully to support a conviction under the statute. The government does not have to show that the doctor knew the prescription was not authorized, regardless of whether the doctor actually wrote it.

As a result, the Department of Justice has brought criminal charges against numerous healthcare workers, testing the legal limits of the legislation. In essence, the approach meant that, regardless of the doctor’s own subjective belief about the prescription’s medical necessity, even when the doctor acted in good faith and honestly believed the controlled substance was needed for a legitimate medical purpose, they were still subject to criminal prosecution if the government could show that the prescription was unauthorized.

In Ruan v. United States, the Supreme Court addressed this matter and held that all components of the crime—including whether the prescription was authorized—must be taken into account when determining whether the mens rea necessary to support a criminal conviction is met.

In other words, the government must now demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt that a doctor intentionally or knowingly dispensed a banned substance while doing so with knowledge that it was unlawful. According to federal law, a distribution must be “given for a valid medical purpose by an individual practitioner working in the regular course of their professional practice” in order to be considered “approved.” After Ruan, the government must establish without a shadow of a doubt that a doctor knew they were prescribing, or intended to prescribe, a banned substance without a valid medical justification.

Two doctors involved in Ruan were found guilty under the law. Xiulu Ruan was found guilty of distributing restricted medications without a valid medical need and beyond the scope of competence. Ruan was found guilty mostly of operating a “pill mill.” In the second case, Shakeel Kahn was found guilty on 18 counts of violating the law for dispensing prescriptions for banned substances, mostly opioids. The district courts’ failure to provide the jury instructions to assess each doctor’s subjective intent and knowledge while prescribing and whether they knew their conduct were unlawful was the main point of contention on appeal.

The doctors could not be found guilty based alone on the fact that the prescriptions themselves were not valid, according to the Supreme Court, hence the jury should have been given instructions to take this into account.

The Supreme Court’s decision has made it more challenging for the government to convict doctors for improperly prescribing drugs in violation of the statute. In addition to the previously required objective criteria, the government’s burden has been increased by the court’s reading of the “unless as authorized” provision.

Previously, the government only needed to demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt that a doctor had intentionally or knowingly dispensed or distributed a controlled substance and that it had not been authorized. Now, the government must also demonstrate beyond a reasonable doubt that the doctor had dispensed or distributed the controlled substance in question while being aware that they were not authorized to do so.

Ruan addressed the actions of two doctors, but the ruling seems to be applicable to all “approved” participants in the controlled substance market. The act is not just for medical professionals. Pharmacists, medication producers, and drug distributors are just a few of the parties that the legislation covers and who could be impacted by the court’s ruling.

Due to the previously existing uncertainty in the law, the government brought proceedings under the act against these additional healthcare providers. Convictions of these parties may be less likely to occur as a result of this additional burden of proof, as well as less likely for the government to pursue.

Ruan appears to have confined itself to criminal prosecutions brought in accordance with the legislation since it construed a federal criminal statute. However, given the nature of the statute, it is still unclear if the verdict would have an impact on federal civil court cases. 8 Similar factual circumstances to those in criminal cases brought under the statute give rise to civil litigation under it. No prohibited substance that is a prescription drug may be supplied without the written prescription of a practitioner, according to the section of the statute that controls civil infractions.

In the civil context, the definition of a proper prescription is based on the same regulation that is used to define what is “allowed” under the criminal sections of the act. It is reasonable to question whether the analysis in Ruan applies to civil litigation for inappropriate prescribing in light of this. A civil defendant may claim that the same intent or knowledge required to prescribe or dispense without authorization in a criminal case would be required to prove a civil violation of the statute when interpreting the statute in a civil context and relying on the same definition of what is “authorized.”

In light of Ruan, a pharmacist facing civil claims under the act might successfully defend their dispensing procedures provided they believed (and could demonstrate) that the targeted prescription was “approved” and the government was unable to show they knew differently. We’ll have to wait and see how this ruling affects the law in related situations. For the time being, doctors can concentrate on giving their patients the best care possible without having to worry as much about facing criminal charges.

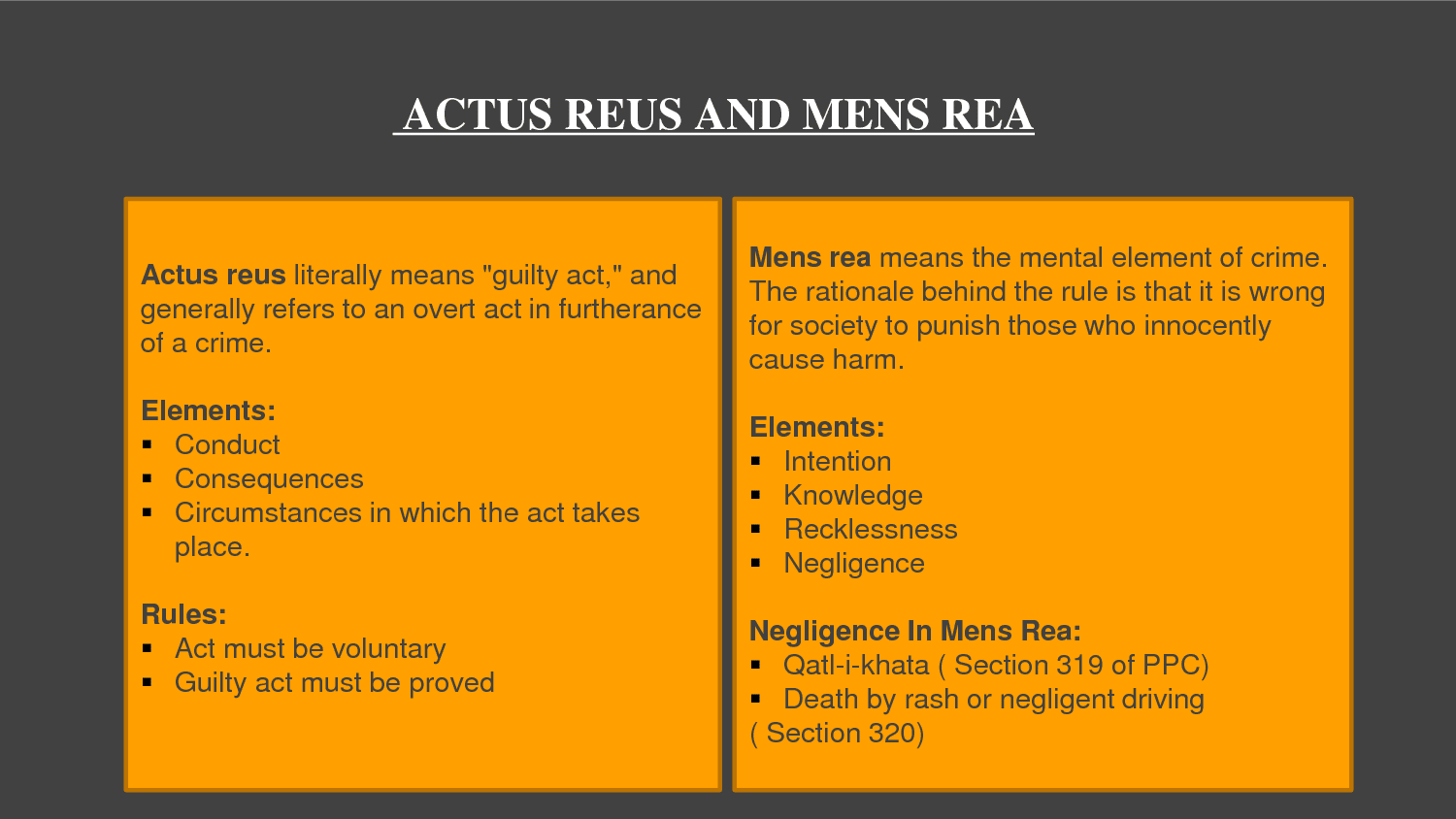

Requirements for Federal Criminal Offenses – Mens Rea

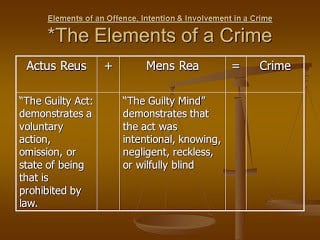

The concept of mens rea, or a “guilty mind,” reflects the idea that a crime generally must consist of not only a proscribed act but also a “mental element” sufficient to warrant punishment. Three questions regularly arise with respect to the mental state required for a given federal crime:

- whether the statute establishing the crime contains a mental-state requirement, or requirements, at all;

- if the statute does contain mental-state requirements, which elements of the offense must meet which requirements; and

- what the mental-state requirements mean. Under federal law, determining the mental state required for commission of a crime necessitates an examination of congressional intent. Congressional intent can be difficult to discern given that federal criminal statutory law (largely codified at Title 18) contains no uniform mens rea standards or generally applicable definitions of mental-state terms.

Because federal statutory law lacks general rules for assessing and applying mens rea terms and requirements across criminal statutes, courts have applied canons of statutory interpretation and developed presumptions specific to mens rea when the state of mind requirement for a federal offense is unclear.

For example, when a criminal statute is silent on the question of what mental state is required, courts will ordinarily apply a presumption in favor of scienter. The presumption counsels that typically some indication is required that Congress intended to dispense with mens rea as an element of a crime, and simply omitting a mens rea term from the statutory language will not be considered adequate evidence of such intent. Assuming the presumption of mens rea applies and calls for a mental-state requirement to be read into a statute that does not expressly contain one, the question becomes what kind of mental state is required.

In this respect, the Supreme Court has said that the presumption requires “only that mens rea which is necessary to separate wrongful conduct from ‘otherwise innocent conduct’”—typically, at least knowledge of certain elements of the offense at issue. With respect to which elements of a crime must meet a given mens rea requirement, the Supreme Court has stated that the presumption in favor of scienter applies to “each of the statutory elements that criminalize otherwise innocent conduct,” though such a distributive approach emphasizing a distinction between elements that make conduct criminal and those that do not can sometimes be difficult to apply in practice.

Finally, regarding what specific mental-state requirements mean, federal law uses dozens of different mens rea terms that are frequently undefined. As such, reference to judicial precedent construing the provision at issue is often required to understand what mental state is required for a particular federal crime. Even so, federal mens rea requirements largely fall into loose categories that may include:

- an awareness of, or conscious purpose to bring about, conduct, a circumstance, or a result that is a required element of the offense (commonly represented by terms such as “intent,” “knowledge,” or “willfulness,” among others), or

- an awareness and disregard of a substantial risk of harm or failure to perceive a substantial risk of harm when a reasonable person would have perceived it (commonly represented by the terms “recklessness” and “negligence,” respectively).

A class of “public welfare” or “regulatory” offenses may actually require no mens rea for their commission at all. For this class of offenses, rather than applying the presumption in favor of scienter, statutory silence is treated as imposing “strict criminal liability” in the sense that one need not have at least knowledge of the facts that make one’s conduct illegal.

Ultimately, several factors may be relevant to a court’s determination of whether a particular criminal statute imposes strict liability, including the nature of the statute and the particular activity or item regulated, the purpose of the criminal prohibition (i.e., punishment of wrongdoing versus protection of the public), the degree to which a defendant will be in a position to ascertain the relevant facts, and the severity of the penalties.

In the past, Congress has considered legislation that would have established default mens rea requirements and application rules in the absence of clear standards in the offense text, and at least one bill (S. 739) has been introduced to this effect in the 117th Congress. Among other things, such legislation would impose standards of either knowledge or willfulness on many offense elements and would require that mens rea terms provided in the text should ordinarily apply to each offense element, with exceptions.

Proponents of such efforts argue that strict-liability offenses and offenses with weak mental-state requirements fail to provide fair notice and represent part of a broader trend of federal over-criminalization. Opponents assert that applying blanket mens rea requirements to existing offenses could permit corporate wrongdoers to evade prosecution and produce unintended consequences.

How Doctors Commit Prescription Fraud

Doctors can commit prescription fraud in many ways. They can knowingly write a prescription for a drug that a patient doesn’t truly need, possibly in return for a bribe, kickback or favor.

They might write prescriptions for people so that those individuals can fill the prescription and then sell the drug back to the physician for personal use or distribution. They might even prescribe one person multiple medications that the individual could never safely take together.

If a pharmacist or insurance company notices questionable prescriptions coming out of one doctor’s practice, an investigation and criminal charges could results. Doctors convicted of prescription fraud could lose the right to practice medicine, in addition to other consequences. Identifying potentially risky behaviors can help you avoid health care fraud charges as a medical professional.

Need Help in a Healthcare Fraud Investigation or You Are Under Investigation in a “Pill Mill’ Case

Contact Heath Hyde directly at 903.439.0000, or via email at Heath@HeathHydeLawyer.com, or fill out our contact form for white collar & government Investigations.

Heath Hyde have recently obtained case dismissals for several clients accuse of ‘Pill Mill’ operations and writing improper prescriptions. Contact Heath Hyde today if you would like to get your case dismissed, or need help if you are currently or about to be investigated for a healthcare fraud investigation, “Pill Mill” case, or you would need help ensuring you are not subject of an investigation.

Call 903.439.0000