In White Collar Investigations, Deferred Prosecution Agreements (DPAs) are used.

Federal white-collar criminal enforcement came under scrutiny in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Much of the criticism was directed at prosecutors who were viewed as being overly lenient with huge financial organizations, with the corporate Deferred Prosecution Agreement being a particular target of opponents (DPA). A DPA is a legal agreement in which the government files criminal charges against a firm, the company agrees to correct the crime (via financial payments and internal reforms), and the charges are eventually dropped.

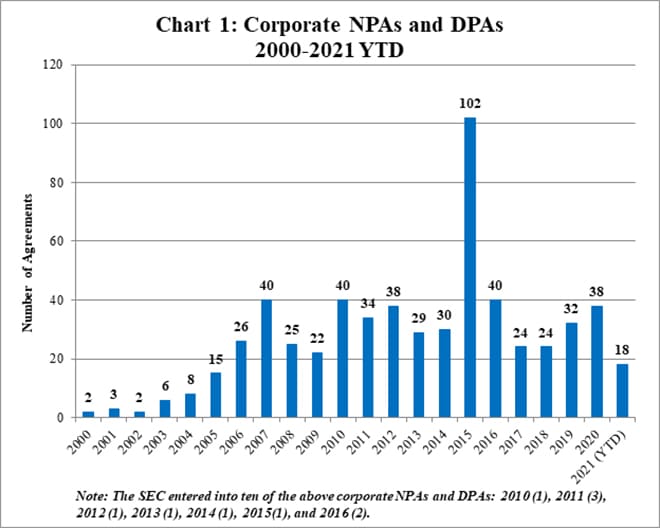

Congress has expressed heightened interest in the use of DPAs (and non-prosecution agreements, or NPAs) as an enforcement weapon in a little-noticed provision of the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). Separate pieces of legislation aiming at boosting anti-money laundering enforcement were included in the NDAA, a measure passed in January 2021 that authorized monies for the military forces.

A little-noticed clause in the bill mandates the Department of Justice (DOJ) to report to Congress every year for the next five years on the use of DPAs and NPAs in BSA cases, with the first report due Jan. 1, 2022. The provision demonstrates a clear understanding of the relevance of DPAs and NPAs in BSA and other white-collar enforcement – as well as a strong desire to be allowed to review DOJ decisions.

The practical and policy grounds for using DPAs and NPAs in white-collar criminal investigations are discussed first in this article. The new reporting clause in the NDAA is then discussed, as well as its relevance to other attempts to improve transparency in DOJ decision-making. Finally, we compare and contrast the current reporting requirement with previous judicial efforts to evaluate DPA provisions.

Deferred Prosecution Agreements

In the Context of DPAs and NPAs

Since the 1990s, the Department of Justice has had written internal standards outlining when federal prosecutors should and should not seek criminal charges against a firm. Principles of Federal Prosecution of Business Organizations, 9-28.210, 9-28.300, 9-28.700, Justice Manual. These regulations are based on a recognition of both the relative simplicity of establishing corporate criminal liability (under the doctrine of respondent superior) and the potentially harsh effects of pursuing a firm on innocent third parties (e.g., employees and creditors).

As a result, depending on the circumstances, each iteration of the DOJ guidelines has contemplated a range of outcomes, including felony prosecution (e.g., if the illegal conduct was widespread and supported by senior management) and declining to prosecute a company (e.g., if the illegal conduct was isolated and limited in scope). Sack and Abramowtiz, “Deferred Prosecution Agreements in Decline? Enforcement Implications,” N.Y.L.J., N.Y.L.J., N.Y.L.J., N.Y.L.J., N.Y.L.J., N.Y.L.J., N.Y (Jan. 5, 2016).

The possibility of leniency benefits the DOJ’s critical law enforcement interests. For example, the Department of Justice’s Criminal Division has adopted policies that establish a presumption of leniency, including the possibility of non-prosecution — but only for companies that self-report misconduct, remediate underlying issues, and fully cooperate with the DOJ’s investigation, including against individual wrongdoers.

Rod Rosenstein, Remarks at the American Conference Institute, for example (Nov. 29, 2018). This was the foundation of the FCPA Pilot Program, which was launched in 2016 and has since grown to become a standard policy in FCPA and other white-collar cases. See Jonathan Sack’s Forbes article, “DOJ Announces It Will Extend FCPA’Pilot Program” (March 13, 2017).

BSA inquiries into the adequacy of a financial institution’s anti-money laundering measures have traditionally been resolved by DPAs (and NPAs). Given the significance of financial institutions to the economy and the potential impact of a bank’s prosecution and guilty plea on innocent third parties, the use of DPAs in this context is unsurprising.

However, in BSA and other white-collar instances, such leniency has drawn some harsh criticism. Sack and Abramowtiz, “White-Collar Enforcement Under Attorney General Eric Holder,” N.Y.L.J., N.Y.L.J., N.Y.L.J., N.Y.L.J., N.Y.L.J., N.Y.L.J (March 3, 2015). One of the criticisms leveled at such transactions is that they shift financial expenses to current shareholders while avoiding accountability for those guilty for corporate malfeasance.

Surprisingly, this critique appears to be focused on the failure to hold individuals accountable for major misconduct rather than the failure to require a firm to enter a guilty plea. This worry about the insufficiency of individual prosecutions has reflected itself in a number of ways, the most notable of which was the Yates Memorandum, which pushed federal prosecutors to pursue charges against individuals before dismissing investigations involving corporate malfeasance in 2015.

“Individual Accountability for Corporate Wrongdoing,” Memorandum from Sally Quillian Yates, Deputy Attorney General, United States Department of Justice, to All United States Attorneys et al (Sept. 9, 2015). This strategy has been criticized for going too far in the opposite direction, pressuring businesses to assist prosecutors in bringing unjustified cases against individuals. “Flaws Emerge in Justice Department Strategy for Prosecuting Wall Street,” Wall Street Journal, Aruna Viswanatha and Dave Michaels (July 5, 2021).

The discussion about corporate leniency programs has waned in the years since the financial crisis. However, the correct way to pursuing corporate wrongdoing remains a contentious topic.

Oversight of DPAs by Congress

The National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), which authorizes military spending, is frequently utilized to pass other laws. The NDAA featured a number of bipartisan provisions this year, including the Corporate Transparency Act (CTA) and the Anti-Money Laundering Act (AMLA), both of which aim to improve the ability to detect and prosecute money laundering, BSA violations, and other related offenses. The CTA compels new and existing U.S. businesses to inform the Treasury Department of their beneficial owners. The AMLA toughens up on recurrent BSA offenders and improves inter-agency coordination in BSA investigations.

As part of the AMLA, Section 6311 of the NDAA mandates the DOJ to send a report to the House and Senate Judiciary Committees, the House Financial Services Committee, and the Senate Banking Committee every year.

- a list of DPAs and NPAs that the Department of Justice “has entered into, altered, or terminated with any person with respect to a violation or alleged violation of the Bank Secrecy Act during the year covered by the report”;

- “the reasons for entering, altering, or terminating” the DPA or NPA;

- “a list of considerations considered by the Attorney General in deciding whether to enter into, alter, or terminate” each agreement; and

- “the extent to which the Attorney General coordinated with the Secretary of the Treasury, Federal functional regulators, or State regulators before to entering into, altering, or terminating any” agreement

Despite the lack of legislative history surrounding 6311, the reporting obligation did not originate in a vacuum. After the financial crisis of 2008, politicians on both the left and right have questioned if DPAs are being used to shield corporate wrongdoers from more accountability and penalties.

For example, in 2016, the Republican Staff of the House Committee on Financial Services published “Too Big To Jail,” a study condemning the use of a DPA to resolve money laundering allegations against HSBC Bank (see https://bit.ly/3hVa903). In a similar spirit, Democrat Senator Elizabeth Warren presented the “Ending Too Big to Jail Act” in 2018, which would have given the judiciary more authority over DPAs. Although the bill did not become law, the issue remained.

Decisions of the Department of Justice are transparent.

The NDAA 6311 reporting requirement creates a number of fascinating concerns for white-collar professionals.

Notably, the DOJ already has a high level of transparency when it comes to the rationale for engaging into corporate DPAs. For many years, the DOJ has issued press releases in conjunction with DPAs and other corporate charging (and some non-charging) decisions that explain the factors that influenced the nature and extent of the government’s leniency — for example, whether the company received credit for self-reporting or remediating misconduct or for cooperating with the investigation.

As stated by then-Assistant Attorney General Leslie Caldwell, this policy extends back to the Obama administration and has been maintained by the Trump administration. Remarks at the 33rd Annual ABA National Institute on White-Collar Crime Conference, Brian A. Benczkowski (March 8, 2019).

Consider the last year’s DPA between the Department of Justice and the Industrial Bank of Korea to resolve Bank Secrecy Act allegations. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of New York (SDNY) stated in a press release that the Bank had agreed to enter into a DPA after conducting a “thorough internal investigation and transactional analysis,” providing “frequent and regular updates to the U.S. Attorney’s Office,” and making employees from other countries available for interviews in the United States. “Manhattan U.S. Attorney Announces Criminal Charges Against Industrial Bank of Korea for Bank Secrecy Act Violations,” according to the article (April 20, 2020).

Given this policy and practice, the law’s requirement for reporting on the “justification” for a DPA or NPA, as well as “the list of criteria considered,” is perplexing. To a considerable extent, the DOJ already makes this information available to the public. This raises problems about what Congress is searching for, whether the executive branch should submit its internal deliberations to Congress, and if the reporting requirement would violate Rule 6(e) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which protects grand jury proceedings’ privacy.

The Department of Justice’s oversight

The reporting requirement in Section 6311 marks a renewed effort by a different branch of the federal government to regulate and potentially limit the use of DPAs by the executive branch. Following earlier criticism of the DOJ’s deals with specific firms, a number of district judges sought to oversee DPAs. District Judge John Gleeson observed the “strong public criticism of the DPA” in United States v. HSBC Bank, No. 12-CR-763, 2013 WL 3306161, at 4, 7 (E.D.N.Y. July 1, 2013), and found power to oversee the DPA’s application in that case, in part to defend the “integrity” of the judicial process.

In United States v. Fokker Services, District Judge Richard Leon expressed similar reservations about giving “the Court’s stamp of approval to… overly-lenient prosecutorial action.” 160, 166 F.Supp.3d 79 F.Supp.3d 79 F.Supp.3d 79 F.S (D.D.C. 2015). See Jonathan Sack’s Forbes article Meet the Fokker (March 12, 2015).

On appeal, these attempts to exercise oversight were dismissed. The Second Circuit ruled in HSBC that Judge Gleeson’s judgment “impermissibly encroached on the Executive’s constitutional obligation to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.” (quoting U.S. Const. art. II, 3) 863 F.3d 125, 129 (2d Cir. 2017).

The D.C. Circuit reversed Judge Leon’s denial of a proposed DPA in Fokker Services, stating that “judicial jurisdiction is at its most limited when examining the Executive’s exercise of discretion over charging determinations.” (D.C. Cir. 2016) 818 F.3d 733, 741 (internal alternations and quotations omitted).

Summary

The President is tasked by the Constitution with “taking [care] that the Law be faithfully executed,” according to the United States Constitution, Art. II, 3. A basic executive authority is the enforcement of federal criminal law, which includes the entry of DPAs. However, the use of prosecutorial discretion in specific instances, particularly those involving financial institutions, is fraught with debate.

Attempts to have DPAs reviewed by the courts were ultimately denied by appellate courts. Section 6311 looks to be yet another attempt to rein in, or at least begin to rein in, executive power. DPAs will almost definitely continue to play a significant role in white-collar crime enforcement. What is unclear is whether 6311 signals a resurgence of criticism of the Department of Justice’s white-collar enforcement policies and actions.

DEFERRED PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS AND NON-PROSECUTION AGREEMENTS are two types of non-prosecution agreements.

Experienced Federal White Collar Defense Attorney

If you’re being investigated for white collar criminal activity, the prospect of criminal litigation may be overwhelming — the threat of punishment is certainly more “real” than ever, with the Department of Justice actively prosecuting white collar cases in an effort to make up for their perceived weakness in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

Despite government prosecutors’ aggressive tendencies in today’s harsh legal context, white collar criminal defendants have a number of options for minimizing or avoiding punishment, including the use of deferred and non-prosecution agreements (DPAs and NPAs)

Using Deferred Prosecution Agreements

The DPAs and NPAs Are Extremely Effective Tools for Avoiding Punishment.

DPAs and NPAs are voluntary agreements in which the prosecutor gives amnesty to the defendant in exchange for cooperation. In essence, a DPA or NPA permits the defendant to avoid criminal penalty in exchange for the prosecutor imposing a lengthy list of conditions that the defendant must meet in order to avoid punishment.

Prosecutors may enter into a DPA with a firm if it is involved in a white-collar lawsuit involving extensive fraud, but only if the company takes steps to rectify its fraudulent acts, develop internal protocol to prevent future fraud, and maybe pay fines.

What Are the Distinctive Features of DPAs and NPAs?

Deferred prosecution agreements are similar to non-prosecution agreements, however there are a few distinctions to be made.

DPAs, in the most basic sense, will result in the prosecution bringing criminal charges against the defendant. The defendant is usually required to confess fault, and fines and reparation payments may be imposed as a result. Furthermore, if you accept a DPA, the prosecution will appoint a “monitoring” official to ensure that you comply with all of the DPA’s requirements.

In general, NPAs are less stringent, and an NPA does not result in any criminal charges (or any admission of fault). NPAs also do not necessitate the presence of a monitoring authority. For many defendants, an NPA is preferred due to the loosened standards. They may discover that the stricter compliance requirements (and acknowledgment of wrongdoing) demanded by a DPA are simply too costly and risk damaging their brand image.

Contact Heath Hyde for Immediate Criminal Defense Assistance

Heath Hyde is a small federal criminal defense business with a large white collar criminal defense practice across the country. Heath has represented a wide spectrum of persons and corporations throughout the years, assisting them in minimizing or avoiding criminal culpability entirely, especially in cases where the defendant may not have many solid legal grounds.

We are fundamentally realistic and detail-oriented litigators who strive to achieve a good outcome for our clients, whether through a vigorous trial defense or by discussions with the prosecution. This dynamic approach is one of the most important aspects of our defense representation.

Call us at 903-439-0000 to speak with a Federal white collar defense attorney about your case, or fill out a case evaluation form on our website at www.heathhydelawyer.com, or email Heath Hyde at Heath@Heathhydelawyer.com to schedule an appointment.